In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, The Texas Lawbook spotlighted Houston partner Sang Shin as he described his experience as an Asian American growing up in North Carolina.

Celebrating AAPI Heritage MonthAs May marks AAPI Heritage Month, Shari Mao and Sang Shin were featured on the Jackson Walker Fast Takes podcast as they shared how their upbringings shaped their careers. During this episode, Sang walks through his family’s experience emigrating from South Korea and the struggles he observed as his parents worked their way through the immigration system, which inspired him to start his own immigration practice. View the episode transcript » |

Here is the full excerpt of Sang’s article, “Channeling Struggles to Create Opportunity,” contributed to The Texas Lawbook:

In 1980, my parents emigrated from South Korea to the United States for a better life – one filled with promise and opportunity. Like many immigrants at the time, they came to the states with very little and worked extremely hard to provide for their family.

For 30 years, my mother owned a laundromat located in a majority Black neighborhood in Charlotte, North Carolina. Over time, the area gentrified and became majority white. She pivoted and turned her store into a dry cleaning and alterations business to adapt to her changing customer base.

My father held many different jobs and would often part ways with his employers because of the cultural and language barrier.

As a result of the struggles they faced, my parents urged me and my sister to keep our heads down and work hard so we could succeed. They wanted a better life for us. They believed that conformance was the best way to achieve success. They did not appreciate, however, that full assimilation is impossible to achieve. Nor did they consider that even if accomplished, perhaps assimilation should not have been the goal: that my culture and heritage was more valuable in shaping what I had to offer – not the other way around.

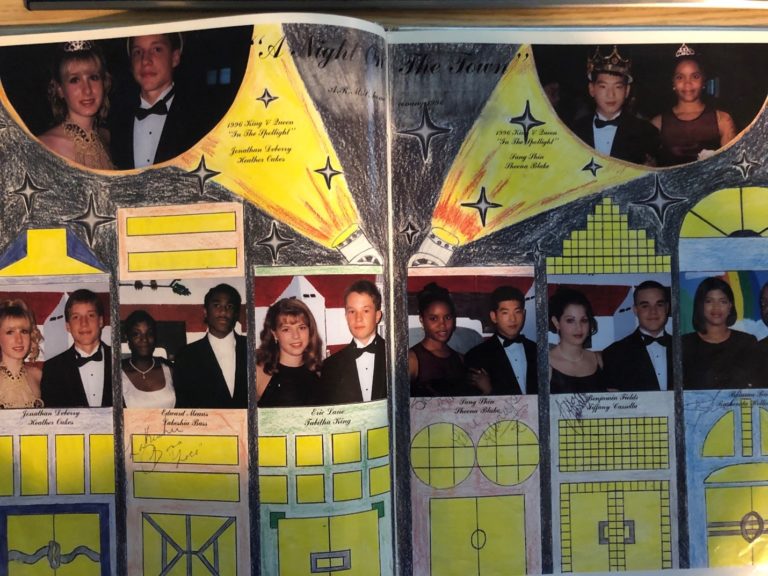

To understand my experience as an Asian American growing up in North Carolina, I have to rewind to 1997. I was in ninth grade. Below is a picture from the school’s yearbook that featured our Homecoming Court. As you can see, there were two homecoming kings and queens. Yours truly was named king … of the “Minority Court.”

In 1997, Sang Shin (upper right corner) was named King of his school’s “minority” Homecoming Court.

In 1997, this was normal and was understood as ensuring both black and white students were able to be homecoming king and queen. In fact, the school system was still working through integration. In my elementary years, I had to attend public schools more than 45 minutes from my home.

The implication that no minority student could be named “Homecoming King” or “Queen,” no qualifier, was lost on me at the time. While I was happy to be considered to be on the court – let alone win – not everyone shared my enthusiasm. Many of the Black students expressed frustration that a non-Black student had won, while the white students perceived it as obvious that I would be a member of the minority court. Interestingly, that year the “Black court” and “minority court” were used interchangeably. Suffice it to say, I felt unwelcome on either side.

Growing up, I often felt this tension – that I did not belong to any community. Not many people looked like me. I was not accepted as white, but I was not considered a “minority” either – perhaps more of an “oddity.” Looking back, this experience still resonates with me today. It is representative of my personal struggles with my cultural identity.

There is a false notion that Asian Americans are privileged, that their parents work hard to pay for tutors and SAT prep courses so their children can excel and get accepted into prestigious universities. This did not apply to me. My parents could not afford to provide those opportunities. I spent many hours helping at the laundromat, supporting my parents at their jobs. My grades suffered. I knew I needed help. I also knew that it was up to me to pave my own path.

Given that my credentials were unimpressive, I was not initially accepted into my alma mater, the University of North Carolina. That didn’t stop me from transferring there the following year. After college, I enrolled at the Charlotte School of Law, an unranked law school, but the only one in the area that offered a night program. For three-and-a-half years, I balanced a full-time job with nighttime courses, boasted a fair GPA, and started the Asian American Law Students Association at the school. Yet, upon graduation, I applied for many of the same jobs as my peers and never got a call back.

Despite these setbacks, I remained determined to become a lawyer, so I relocated to Houston in 2012 to work at a local immigration boutique firm. It was in Houston – the most culturally rich and diverse city in the nation – that I found a sense of community and belonging.

When I first moved to Texas, I wanted to get involved with a professional network. The Asian American Bar Association of Houston was the first one that came to mind. It was created for the common purpose of community and to serve the needs of the Asian American community. This mission drew me in. Over the last decade, I have had the pleasure of serving on multiple committees, was named president in 2018, and am now Chair of the Board of Directors, a role I have proudly held since 2019. It is through my participation in the AABA of Houston that I am able to connect with fellow Asian American attorneys and help those who experienced similar obstacles in life.

When I first moved to Texas, I wanted to get involved with a professional network. The Asian American Bar Association of Houston was the first one that came to mind. It was created for the common purpose of community and to serve the needs of the Asian American community. This mission drew me in. Over the last decade, I have had the pleasure of serving on multiple committees, was named president in 2018, and am now Chair of the Board of Directors, a role I have proudly held since 2019. It is through my participation in the AABA of Houston that I am able to connect with fellow Asian American attorneys and help those who experienced similar obstacles in life.

It was after I lateraled to Jackson Walker in 2019 that I was able to grow further as a professional, develop my practice and, more importantly, grow my voice and platform for others – especially for those, like me, who have had experiences holding them back from their full potential. I am thankful to Jackson Walker for believing in me and allowing me to represent them.

My upbringing – as an immigrant who grew up in a place where there wasn’t much cultural diversity or support – inspires me each day to work with the AABA of Houston to create opportunities for Asian Americans whose paths to success may resemble my own. Paths that are not straight and obvious, but that are unconventional and winding. I am so proud that the AABA of Houston is working hard to make an impact so that individuals like myself can use our experiences to help our community and to provide the support that future generations need to succeed.

This article, which Sang Shin authored in May 2022, was originally posted in The Texas Lawbook.

Meet Sang

Meet Sang

Sang Shin is a business immigration attorney with broad experience managing immigration matters for companies, individuals, investors and institutions through the U.S. and internationally. Sang handles a wide range of nonimmigrant visas and petitions, and also provides advanced and strategic advice to clients on a variety of immigrant visas and labor certification (PERM). He handles family-based cases and U.S. citizenship matters, and regularly represents companies in connection with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), U.S. Department of State (DOS), and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Form I-9 (Employment Eligibility Verification) audits. He works with international companies entering the U.S. market for the first time, helping them navigate the ever-changing U.S. legal landscape and helps with seamless market entry. He also advises start-ups, entrepreneurs, and high net-worth individuals regarding investment-based U.S. immigration opportunities.

Sang has been recognized among The Best Lawyers in America in the area of Immigration Law since 2021 and Houstonia Magazine’s list of the top lawyers in immigration in “Best of Houstonia” in 2021. In addition, he was honored in 2020 with the Best Under 40 Award by the Asian Pacific Interest Section (APIS) of the State Bar of Texas.

Outside of his practice, Sang serves as Chair of the Board of Directors of the Asian American Bar Association of Houston, a trustee of the Asian American Bar Foundation of Houston, the secretary of the Asian Pacific Islander Section of the State Bar of Texas, and a council member of the Immigration Section of the State Bar of Texas.